Story courtesy of WPLN, by Alexis Marshall

Over a dozen Tennessee State University students are descending more than a hundred feet underground, outfitted with knee pads, helmets and headlamps.

This fall 2022 trip is part of a national program to get more students from Historically Black Colleges and Universities involved in the outdoors, and WPLN News is tagging along for the journey.

TSU student Aria McElroy serves as a college ambassador for the National Park Trust and the nonprofit HBCUs Outside. She recruited classmates from an on-campus club to join the excursion.

“I feel like it’s really good for students to be able to take the initiative to get their peers outside, because if it’s like someone older than you or like a faculty member, you might not be as interested.”

McElroy says she felt called to become a college ambassador after an internship in the Rocky Mountains last summer.

“It was just an opportunity for me and other students to get back outside and rekindle the love that they may have had — or just have a new love that they didn’t even know that they had.”

Together, the sponsoring organizations provide funding, resources and mentorship to get more Black students comfortable with things like hiking and camping.

TSU is one of four historically Black schools where the program is rolling out.

Arriving at Mammoth Cave

On a drizzly morning, students gather at the top of a steep staircase leading down into the cave. Rangers and a research professor from the school explain some of the main features.

Sophomore Blake Wright asks about the wildlife.

“What’s the largest animal that lives in the cave today?”

“The largest things that you’re going to see in the cave today are probably bats,” Jakaitis says. Another student inquires whether the bats could pose a problem to the group.

Specialist Rick Toomey offers reassurance.

“I’m going to say the bats won’t bother us,” he says. “The raccoons and rats won’t bother us either.”

The descent

Climbing down into the caverns, students pass a tall, trickling waterfall. They tread through tunnels carved out over millions of years.

“I grew up around suburbs, so I wasn’t in any rural areas,” says Wright. He came into the day hoping to get a deeper understanding of caves. “I enjoy listening to, learning about, just the nature around us, how the ecosystem works and correlates.”

You can see the awe in students’ faces looking at an enormous naturally vaulted ceiling or a large cluster of stalactites and stalagmites.

Off the main path now, they flip on their headlamps and carefully descend farther into the caverns. A few get startled at the sight of a cave cricket, which looks a lot like a spider.

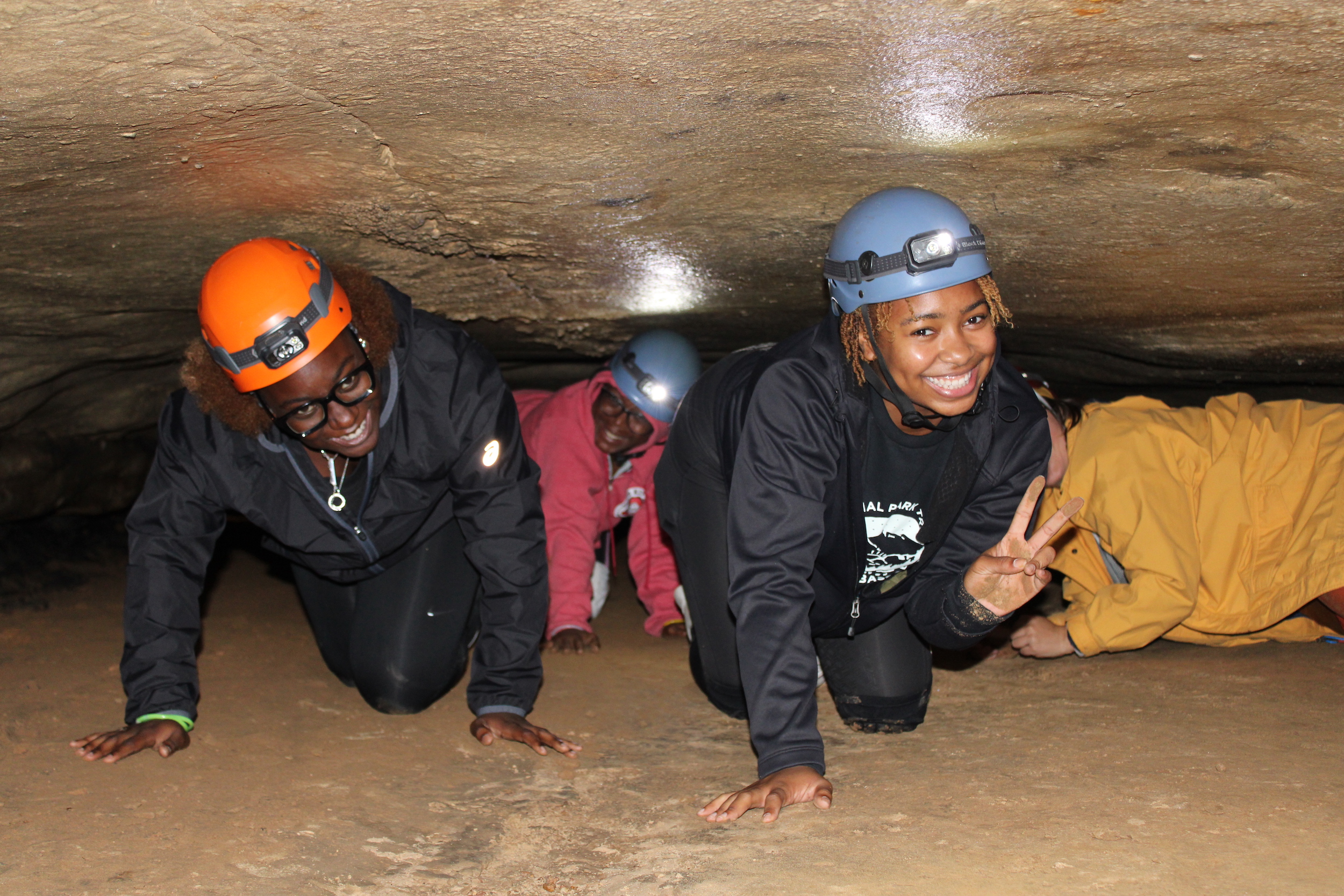

“This is a crawly passage!” Toomey announces.

Students pull up their knee pads. On hands and bellies, they scuttle across the reddish, sandy floor of the cave to see shark teeth, and the signature of an old explorer.

Black history at Mammoth Cave

Students also learn about darker chapters in the cave’s history. The caverns were once used to mine saltpeter for gunpowder. And many enslaved African Americans did the labor-intensive work.

Stephen Bishop was one of the enslaved people forced to give tours of the cave in the mid-1800s. Because of his work, he developed an unparalleled knowledge of the caverns.

“One of his most notable accomplishments is a work of mapping the cave,” says Jakaitis. “And over the course of a couple of weeks, Stephen created a map that you see here almost entirely written, drawn from memory.”

This was the first time many of the students had ever heard about Bishop — or any of the Black history associated with the cave.

History is a big part of why this program exists. Segregation barred African Americans from having equal access to public green spaces. And today, the outdoor recreation industry is overwhelmingly white. Researchers refer to this kind of inequity as the “nature gap.”

Diversifying the outdoors

Ron Griswell, the founder of HBCUs Outside, says reestablishing those historic bonds with nature is especially important for Black students.

“A lot of us don’t have the connections like our ancestors did when we were so tied spiritually and physically to nature. It’s kind of disheartening,” Griswell says.

“I want HBCUs to be the first step in not only diversifying the outdoors, but reclaiming these spaces for joy and ushering in a new, diverse population of stewards.”

Wright may well be one of those stewards. He says he’s eager to continue getting outdoors.

“I want to explore this cave again, just to get another experience and as well explore around the cave, like outside and above. See what the nature has to offer above ground.”

In fact, he says he’s coming back next semester for a fishing trip.